Войска Alexander'а

Сообщений 241 страница 270 из 354

Поделиться24226.11.21 11:35:32

Поделиться24704.12.21 18:56:34

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swedish alliance were Peter I of Russia, Frederick IV of Denmark–Norway and Augustus II the Strong of Saxony–Poland–Lithuania. Frederick IV and Augustus II were defeated by Sweden, under Charles XII, and forced out of the alliance in 1700 and 1706 respectively, but rejoined it in 1709 after the defeat of Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava. George I of Great Britain and the Electorate of Hanover joined the coalition in 1714 for Hanover and in 1717 for Britain, and Frederick William I of Brandenburg-Prussia joined it in 1715.

Charles XII led the Swedish army. Swedish allies included Holstein-Gottorp, several Polish magnates under Stanisław I Leszczyński (1704–1710) and Cossacks under the Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1708–1710). The Ottoman Empire temporarily hosted Charles XII of Sweden and intervened against Peter I.

The war began when an alliance of Denmark–Norway, Saxony and Russia, sensing an opportunity as Sweden was ruled by the young Charles XII, declared war on the Swedish Empire and launched a threefold attack on Swedish Holstein-Gottorp, Swedish Livonia, and Swedish Ingria. Sweden parried the Danish and Russian attacks at Travendal (August 1700) and Narva (November 1700) respectively, and in a counter-offensive pushed Augustus II's forces through the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to Saxony, dethroning Augustus on the way (September 1706) and forcing him to acknowledge defeat in the Treaty of Altranstädt (October 1706). The treaty also secured the extradition and execution of Johann Reinhold Patkul, architect of the alliance seven years earlier. Meanwhile, the forces of Peter I had recovered from defeat at Narva and gained ground in Sweden's Baltic provinces, where they cemented Russian access to the Baltic Sea by founding Saint Petersburg in 1703. Charles XII moved from Saxony into Russia to confront Peter, but the campaign ended in 1709 with the destruction of the main Swedish army at the decisive Battle of Poltava (in present-day Ukraine) and Charles' exile in the Ottoman town of Bender. The Ottoman Empire defeated the Russian-Moldavian army in the Pruth River Campaign, but that peace treaty was in the end without great consequence to Russia's position.

After Poltava, the anti-Swedish coalition revived and subsequently Hanover and Prussia joined it. The remaining Swedish forces in plague-stricken areas south and east of the Baltic Sea were evicted, with the last city, Riga, falling in 1710. The coalition members partitioned most of the Swedish dominions among themselves, destroying the Swedish dominium maris baltici. Sweden proper was invaded from the west by Denmark–Norway and from the east by Russia, which had occupied Finland by 1714. Sweden defeated the Danish invaders at the Battle of Helsingborg (1710). Charles XII opened up a Norwegian front but was killed in the Siege of Fredriksten in 1718.

The war ended with the defeat of Sweden, leaving Russia as the new dominant power in the Baltic region and as a new major force in European politics. The Western powers, Great Britain and France, became caught up in the separate War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), which broke out over the Bourbon Philip of Anjou's succession to the Spanish throne and a possible joining of France and Spain. The formal conclusion of the Great Northern War came with the Swedish-Hanoverian and Swedish-Prussian Treaties of Stockholm (1719), the Dano-Swedish Treaty of Frederiksborg (1720), and the Russo-Swedish Treaty of Nystad (1721). By these treaties Sweden ceded its exemption from the Sound Dues[17] and lost the Baltic provinces and the southern part of Swedish Pomerania. The peace treaties also ended its alliance with Holstein-Gottorp. Hanover gained Bremen-Verden, Brandenburg-Prussia incorporated the Oder estuary (Stettin Lagoons), Russia secured the Baltic Provinces, and Denmark strengthened its position in Schleswig-Holstein. In Sweden, the absolute monarchy had come to an end with the death of Charles XII, and Sweden's Age of Liberty began.

Поделиться24805.12.21 07:33:08

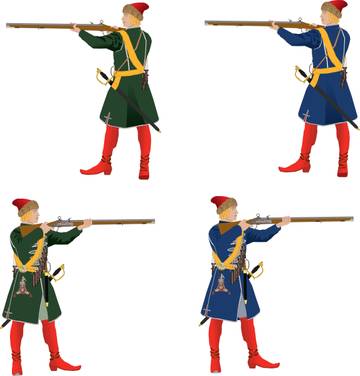

По мотивам Северной Войны (1700-1721)

The Great Northern War

Citation: C N Trueman "The Great Northern War"

historylearningsite.co.uk. The History Learning Site, 28 May 2015. 4 Dec 2021.

The Great Northern War lasted from 1700 to 1721. The Great Northern War was fought between Sweden’s Charles XII and a coalition lead by Peter the Great. By the end of the war, Sweden had lost her supremacy as the leading power in the Baltic region and was replaced by Peter the Great’s Russia.

The Russian Civil War

Peter the Great

The Great Northern War had a number of distinct phases: 1700 to 1706; 1707 to 1709; 1709 to 1714; 1714 to 1718 and 1718 to 1721.

Though the Great Northern War started in 1700, the causes of it had been fermenting throughout the 1690’s. An anti-Swedish coalition was created from 1697 to 1699 and included Russia, Denmark and Saxony-Poland. All three states believed that a fifteen years old king – Charles XII – would be an soft target. They also had a shared belief that Sweden by the 1690’s was a spent force and that her territory was waiting to be cut up by a superior force.

Charles V of Denmark wanted to regain Scania and other territories on the Swedish mainland lost by Denmark to Sweden during the Seventeenth Century. Denmark also wanted to remove Swedish troops from the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp – a Swedish satellite state.

Augustus II of Saxony-Poland was known as Augustus the Strong. He was also the Elector Frederick Augustus of Saxony and in 1697 he was elected king of Poland – hence his combined title of Saxony-Poland. Augustus wanted to conquer Livonia to put an end once and for all to Swedish economic predominance in the Baltic. He wanted to develop Poland’s industrial base by using Poland’s raw materials and Saxony’s economic know-how. However, he could not do this while Sweden remained a commercial rival in the Baltic.

Peter the Great simply wanted a foothold in the Baltic as a move towards greatness in the region. Russia could never be great in the Baltic while Sweden was pre-eminent especially as Sweden possessed Karelia, Ingria and Estonia – thus blocking Russia’s advance west.

This anti-Swedish alliance was knitted together by J R von Patkul and other anti-Swedish noblemen living in Livonia. The was started badly for the alliance.

1700 to 1706:

In March 1700, the Danes invaded Holstein-Gottorp. The Swedes, aided by an Anglo-Dutch fleet as well as their own navy, invaded Zeeland and threatened to overrun Copenhagen. In August 1700, Denmark withdrew from the war via the Treaty of Traventhal.

While Sweden was fighting Denmark, Augustus invaded Livonia but quickly withdrew when Charles XII transferred his army to Livonia from Denmark.

Charles was now free to attack Russia who were besieging Narvia and Ingria. 8,000 Swedes destroyed a Russian army of 23,000 in November 1700 – this was to give Charles XII legendary military status and it also confirmed to western nations that Russia under Peter the Great was backward.

From 1700 to 1706, Charles spent time in Poland building up a firm military base there before his planned invasion of Russia. Charles courted anti-Saxon and anti-Russian Polish nobles for their support. Charles’ campaign in Poland lead to him conquering Warsaw in May 1702, and he defeated a Polish-Saxon army at Kliszow in June 1703. Thorn was also captured in 1703. After such military success, Charles organised the election of a puppet leader – Stanislas Leszczynski. He became king of Poland in July 1704.

Charles signed the Treaty of Warsaw with Poland in February 1705 which was for peace and commerce and defeated and he defeated the Saxons at the Battle of Fraustadt in February 1706. By Spring 1706, Charles was in control of Poland having forced out both the Russians and the Saxons. The final blow came in September 1706 when Augustus II recognised Stanislas as the king of Poland in the Treaty of Altranstädt and allowed the Swedish Army to winter in Saxony.

While Charles XII had been concentrating on Poland, Peter the Great had made incursions into parts of the Baltic controlled by Sweden; namely, Dorpat and Narva – both in 1704. However, such was the military status of Charles, that Peter ceded these conquests in order to make peace. Charles would not accept this and considered Russia a permanent danger to Sweden in the Baltic. He prepared a campaign against Russia – a march on Moscow.

1717 to 1709:

The invasion of Russia started in 1707. Charles had planned for a two-pronged attack. Charles XII, himself, invaded Russia via Smolensk while Count Lewenhaupt invaded Russia via Riga. From 1707 through to 1708, Peter the Great withdrew his forces. Peter made his first stand at Holowczyn in July 1708. The Swedes won but it was at a price. As Peter withdrew, he used a scorched earth policy destroying anything that might be of value to an advancing army.

Charles did not follow Peter. Instead, the Swedish army wintered in the Ukraine. There was a logic to this as Charles hoped to link up with Mazepa, the Hetman of the Ukraine Cossacks, who was seeking to build an independent Cossack state and, therefore, saw Peter as a potential enemy who needed to be defeated. Charles also hoped to build an anti-Russian alliance with Devlet-Girei III, the Khan of the Crimea. Charles was confident that this group of three – the Swedes, the Cossacks and the Crimeans – would defeat Peter.

However, Devlet-Girei III was forced to remain neutral. His master was the Sultan of Turkey and the Sultan did not want to be embroiled in a war that he felt he would only lose out if he joined in or gave his blessing for one of his underlings to get involved. Mazepa of the Cossacks, was simply not in a military position to assist Charles. Therefore, the alliance came to nothing. Charles also had other problems to face.

The winter of 1708 to 1709 was one of the worst on records and had a major impact on Sweden’s army that was wintering in the Ukraine.

Also, the advance of Lewenhaupt was stopped at the Battle of Lesnaya in 1708 where he lost his entire supply column.

Charles XII lead a weakened and under-equipped army into Russia. He also had to lead his army on a stretcher as he had been shot in the foot during a skirmish. In June/July 1709, Sweden suffered a serious military defeat at the Battle of Poltava. Many Swedish soldiers were killed and those who were not surrendered at Perevolochna.

The defeat immediately turned around the position Sweden and Russia held in Europe. After this one decisive battle, Sweden was no longer supreme in eastern Europe. The victory put Peter the Great where he wanted to be – dominant in eastern Europe and a power to be reckoned with. Charles had to escape to Turkey.

1709 to 1714:

Charles now found that he could not return to Sweden. All the potential routes were fraught with danger. As a result, Charles stayed at Bender, Bessarabia in Turkey. With Charles isolated, the alliance of Denmark, Poland and Russia revived itself.

Augustus reclaimed his title in Poland as Stanislas fled.

Demark invaded Scania in 1710 but was repelled.

Russia continued her conquest of the Baltic states and Finland. Russia defeated the Swedish navy at Hangö in July 1714 and had the potential to invade Sweden itself.

In the absence of Charles, Sweden was governed by the Swedish Council. They raised a new army which was sent to North Germany in preparation for an attack on Poland. However, Sweden had come to rely on mercenaries and the attempt to produce an army in a very short space of time failed. The army got to northern Germany but it became stuck there as the navy of Denmark destroyed the transport ships used to supply them. With few supplies and little chance of getting back to Sweden, this army surrendered against a combined Russian/Danish/Saxon force at Tanning, Holstein in May 1713.

In Turkey, Charles XII persuaded the Sultan to launch an attack on Russia in the south at the same time as Sweden was launching an attack on Russia in the north. In fact, just one of the major problems Charles faced was lack of communications with Sweden. After Tanning, Sweden simply could not produce an army of any substance. However, the Sultan’s attack was successful in that Russia was defeated at the River Pruth and the Sultan got effective control of the Black Sea and gained Azov. In June 1713, the Sultan signed a settlement with Russia which guaranteed peace between the two for 25 years.

1714 to 1718:

Charles was no longer welcome in Turkey and he made his way to Stralsund in Pomerania. Stralsund and Wismar were the only two possessions Sweden had in northern Germany. For the next few years Charles attempted to make alliances with numerous states – including recent enemy states. It is difficult to know what Charles’ plan was but some believe that he had no intention of maintaining peace and only a desire for Sweden to get back her reputation and status in eastern Europe. In this sense, it seems that Charles was willing to negotiate with any state but probably had no desire to keep to the terms of whatever treaty he signed. Some historians believe that Charles was becoming more and more divorced from reality and that he refused to accept that Sweden’s golden days as the dominant state in eastern Europe were over.

In 1715, two more state joined the alliance against Sweden – Brandenburg and Hanover. Stralsund fell in 1715 and Wismar in 1716. By 1718, Charles had somehow managed to put together an army of 60,000 men. He invaded Norway but was killed at Fredriksheld in late 1718.

1718 to 1721:

The death of Charles XII removed a major stumbling block in the peace process. Charles could not accept that Sweden was a spent force and that the dominant state in eastern Europe was Russia. It is not clear what he intended when he invaded Norway. In the previous 18 years, Norway had not been a problem to Sweden; if Charles had intended to use Norway as a base to attack Denmark, it was a failure.

Fear of Russia extended further than the Baltic. Britain and France were both concerned at the potential extent of Russia’s power and as a result of this, pressure was brought to bear for peace treaties to bring stability to the region as it was reckoned that Russia would use war as a lever to expand. She would have found it more difficult to do so if there was peace in the area.

Four peace treaties brought apparent stability to the Baltic:

Treaty of Stockholm

November 1719 Signed between Sweden and Hanover. Sweden handed over Bremen and Verden to Holstein in return for financial and naval support. The Elector of Hanover was George I.

Treaty of Stockholm

Jan/Feb 1720 Signed between Sweden and Brandenburg. Sweden ceded Stettin, South Pomerania, the islands of Usedom and Wollin in return for money.

Treaty of Fredriksborg

July 1720 Signed between Sweden and Denmark. Sweden gave up her exception from paying taxes to use the Sound. She also gave up Holstein-Gottorp.

Treaty of Nystad

Aug/Sept 1721 Signed between Sweden and Russia. Sweden ceded Livonia, Estonia and Ingria while Russia returned Finland (except Kexholm and parts of Karelia)

Sweden and Poland signed a peace treaty in 1731.

Поделиться24907.12.21 23:13:28

По мотивам Северной Войны (1700-1721)

Share Share

Share Share

Петр Первый вел активную внешнюю политику, стараясь укрепить мощь Российского государства. Он понимал, насколько важным было иметь выход к Балтийскому морю, ведь для международной торговли с северными странами Европы у России имелся всего один порт – Архангельск. Задача получения выхода к Балтийскому морю стала ведущей причиной присоединения Петра к коалиции под названием Северный Союз и вступления в Северную войну. Одной из первых крупных битв стало сражение под Нарвой. История сохранила второе название этого кровопролитного боя – Нарвская конфузия, поскольку русская армия потерпела сокрушительное поражение под Нарвой. Почему же исход битвы оказался столь плачевным и какие уроки сумел извлечь царь из этого крайне неудачного события?

картина

М. Ю. Шаньков – Карл XII под Нарвой

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ

1 Ход событий

2 Итоги

3 Причины поражения

Ход событий

Бой произошел между русскими и шведами 19 ноября 1700 года. Нарва представляла собой прекрасно защищенную крепость, стоящую на берегу Финского залива. Русское командование понадеялось на численное превосходство (в распоряжении русских генералов было 35 тысяч человек против 25 тысяч шведов).

Изначально в крепости находился небольшой гарнизон, однако шведское командование, быстро сориентировавшись в ситуации, направило своим поддержку. Сам король Карл XII прибыл в крепость, чтобы личным примером вдохновлять солдат. В это время он еще был совсем юным монархом, и опыт ему заменяли храбрость и отчаянная уверенность в своих силах.

Шведские войска, прибывшие в помощь гарнизону, высадились в районе Ревеля (Пярну). Однако даже после этого численное превосходство русских было очевидно.

Нападающие выстроились в линию длиной в 7 км. Слабость такой организации заключалась в том, что эта линия была очень тонкой, а за ней не стояли резервные войска. Эта линия двинулась к Нарвской цитадели, стараясь подойти с правого фланга. Там был мост через реку Нарва. Вступив на мост, российские войска начали было активное движение вперед. Однако мост под тяжестью людской массы рухнул. Казалось бы, атака захлебнулась, но в этот момент подоспели Преображенский и Семеновский полки. Закипело сражение, длившееся несколько часов. Наконец, когда уже стемнело, и обе стороны выбились из сил, начались мирные переговоры. Почему Карл пошел на это? Король Швеции еще не был уверен в своей победе, хотя все данные говорили о том, что русские войска разгромлены. Он опасался подхода новых сил и возобновления битвы, понимая, что новый бой может и не выдержать: оборонявшаяся сторона очень устала, свежего подкрепления взять было неоткуда.

Итоги

Битва под Нарвой, состоявшаяся в 1700 году, завершилась победой шведов. Русская армия потерпела поражение. Потери русских составили 8 тысяч человек. При этом погибли многие офицеры из высшего командования. Шведы же потеряли всего 3000 человек. Карл проявил великодушие победителя, позволив русским спокойно вернуться домой – их не забрали в плен. Правда, условие это было соблюдено с нарушениями – Карл не смог сдержать свое слово.

Причины поражения

Петр проанализировал причины поражения русских войск в Нарвской битве и принял меры к исправлению ситуации. Объяснить поражение армии Петра оказалось несложно: в ходе войны и в ходе этого крупного сражения, в частности, выяснилось, что русская армия плохо организована и обучена. Не хватало опытного руководства, страдало качество подготовки рядового состава, недоставало боевых орудий.

Вторая причина заключалась в допущенной Петром ошибке: он уехал накануне даты, когда должно было начаться сражение, оставив армию под началом полководца герцога де Кроа. Несмотря на то что семеновцы и преображенцы показали особую стойкость, да и главнокомандующий делал все, что от него зависело, личное присутствие царя могло бы развернуть ситуацию в другую сторону и, возможно, принести благоприятный результат.

После Нарвской битвы, которая показала необходимость перемен, Петр принял решение о реорганизации вооруженных сил. Состоялась реформа армии, в результате которой последняя стала регулярной. Среди мужчин в возрасте от 17 до 35 лет проводился рекрутский набор.

Особое внимание Петр уделил увеличению базы вооружения. После сражения при Нарве начался сбор церковных колоколов, которые переплавляли в пушки. В итоге армия пополнилась орудиями в количестве 16 тысяч.

Реформа быстро принесла ощутимые плоды: в 1704 году состоялось сражение под Дерптом, и крепость была взята. Несколькими месяцами позже Петр лично принимал участие в новой осаде Нарвы, и русское войско одержало полную и безусловную победу. Взятие Нарвы наглядно продемонстрировало, что русское войско обрело силу и боеспособность. В распоряжении русского императора теперь была регулярная армия, на которую государство могло смело рассчитывать.

Поделиться25511.12.21 20:13:18

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swedish alliance were Peter I of Russia, Frederick IV of Denmark–Norway and Augustus II the Strong of Saxony–Poland–Lithuania. Frederick IV and Augustus II were defeated by Sweden, under Charles XII, and forced out of the alliance in 1700 and 1706 respectively, but rejoined it in 1709 after the defeat of Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava. George I of Great Britain and the Electorate of Hanover joined the coalition in 1714 for Hanover and in 1717 for Britain, and Frederick William I of Brandenburg-Prussia joined it in 1715.

Charles XII led the Swedish army. Swedish allies included Holstein-Gottorp, several Polish magnates under Stanislaus I Leszczyński (1704–1710) and Cossacks under the Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1708–1710). The Ottoman Empire temporarily hosted Charles XII of Sweden and intervened against Peter I.

The war began when an alliance of Denmark–Norway, Saxony and Russia, sensing an opportunity as Sweden was ruled by the young Charles XII, declared war on the Swedish Empire and launched a threefold attack on Swedish Holstein-Gottorp, Swedish Livonia, and Swedish Ingria. Sweden parried the Danish and Russian attacks at Travendal (August 1700) and Narva (November 1700) respectively, and in a counter-offensive pushed Augustus II's forces through the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to Saxony, dethroning Augustus on the way (September 1706) and forcing him to acknowledge defeat in the Treaty of Altranstädt (October 1706). The treaty also secured the extradition and execution of Johann Reinhold Patkul, architect of the alliance seven years earlier. Meanwhile, the forces of Peter I had recovered from defeat at Narva and gained ground in Sweden's Baltic provinces, where they cemented Russian access to the Baltic Sea by founding Saint Petersburg in 1703. Charles XII moved from Saxony into Russia to confront Peter, but the campaign ended in 1709 with the destruction of the main Swedish army at the decisive Battle of Poltava (in present-day Ukraine) and Charles' exile in the Ottoman town of Bender. The Ottoman Empire defeated the Russian-Moldavian army in the Pruth River Campaign, but that peace treaty was in the end without great consequence to Russia's position.

After Poltava, the anti-Swedish coalition revived and subsequently Hanover and Prussia joined it. The remaining Swedish forces in plague-stricken areas south and east of the Baltic Sea were evicted, with the last city, Riga, falling in 1710. The coalition members partitioned most of the Swedish dominions among themselves, destroying the Swedish dominium maris baltici. Sweden proper was invaded from the west by Denmark–Norway and from the east by Russia, which had occupied Finland by 1714. Sweden defeated the Danish invaders at the Battle of Helsingborg (1710). Charles XII opened up a Norwegian front but was killed in the Siege of Fredriksten in 1718.

The war ended with the defeat of Sweden, leaving Russia as the new dominant power in the Baltic region and as a new major force in European politics. The Western powers, Great Britain and France, became caught up in the separate War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), which broke out over the Bourbon Philip of Anjou's succession to the Spanish throne and a possible joining of France and Spain. The formal conclusion of the Great Northern War came with the Swedish-Hanoverian and Swedish-Prussian Treaties of Stockholm (1719), the Dano-Swedish Treaty of Frederiksborg (1720), and the Russo-Swedish Treaty of Nystad (1721). By these treaties Sweden ceded its exemption from the Sound Dues[17] and lost the Baltic provinces and the southern part of Swedish Pomerania. The peace treaties also ended its alliance with Holstein-Gottorp. Hanover gained Bremen-Verden, Brandenburg-Prussia incorporated the Oder estuary (Stettin Lagoons), Russia secured the Baltic Provinces, and Denmark strengthened its position in Schleswig-Holstein. In Sweden, the absolute monarchy had come to an end with the death of Charles XII, and Sweden's Age of Liberty began.[17]

Contents

1 Background

2 Opposing parties

2.1 Swedish camp

2.2 Allied camp

2.3 Army size

3 1700: Denmark, Riga and Narva

4 1701–1706: Poland-Lithuania and Saxony

5 1702–1710: Russia and the Baltic provinces

6 Formation of a new anti-Swedish alliance

7 1709–1714: Ottoman Empire

8 1710–1721: Finland

9 1710–1716: Sweden and Northern Germany

10 1716–1718: Norway

11 1719–1721: Sweden

12 Peace

13 See also

14 Sources

14.1 Notes

14.2 Citations

14.3 Bibliography

14.4 Further reading

14.4.1 Other languages

Background

Further information: Dominium maris baltici

Between the years of 1560 and 1658, Sweden created a Baltic empire centred on the Gulf of Finland and comprising the provinces of Karelia, Ingria, Estonia, and Livonia. During the Thirty Years' War Sweden gained tracts in Germany as well, including Western Pomerania, Wismar, the Duchy of Bremen, and Verden. During the same period, Sweden conquered Danish and Norwegian provinces north of the Sound (1645; 1658). These victories may be ascribed to a well-trained army, which despite its comparatively small size, was far more professional than most continental armies, and also to a modernization of administration (both civilian and military) in the course of the 17th century, which enabled the monarchy to harness the resources of the country and its empire in an effective way. Fighting in the field, the Swedish army (which during the Thirty Years' War contained more German and Scottish mercenaries than ethnic Swedes, but was administered by the Swedish Crown[18]) was able, in particular, to make quick, sustained marches across large tracts of land and to maintain a high rate of small arms fire due to proficient military drill.

However, the Swedish state ultimately proved unable to support and maintain its army in a prolonged war. Campaigns on the continent had been proposed on the basis that the army would be financially self-supporting through plunder and taxation of newly gained land, a concept shared by most major powers of the period. The cost of the warfare proved to be much higher than the occupied countries could fund, and Sweden's coffers and resources in manpower were eventually drained in the course of long conflicts.

The foreign interventions in Russia during the Time of Troubles resulted in Swedish gains in the Treaty of Stolbovo (1617). The treaty deprived Russia of direct access to the Baltic Sea. Russian fortunes began to reverse in the final years of the 17th century, notably with the rise to power of Peter the Great, who looked to address the earlier losses and re-establish a Baltic presence. In the late 1690s, the adventurer Johann Patkul managed to ally Russia with Denmark and Saxony by the secret Treaty of Preobrazhenskoye, and in 1700 the three powers attacked.

Opposing parties

Charles XII of Sweden (left) and Peter I of Russia (right)

Swedish camp

Charles XII of Sweden[nb 1] succeeded Charles XI of Sweden in 1697, aged 14. From his predecessor, he took over the Swedish Empire as an absolute monarch. Charles XI had tried to keep the empire out of wars, and concentrated on inner reforms such as reduction and allotment, which had strengthened the monarch's status and the empire's military abilities. Charles XII refrained from all kinds of luxury and alcohol and usage of the French language, since he considered these things decadent and superfluous. He preferred the life of an ordinary soldier on horseback, not that of contemporary baroque courts. He determinedly pursued his goal of dethroning his adversaries, whom he considered unworthy of their thrones due to broken promises, thereby refusing to take several chances to make peace. During the war, the most important Swedish commanders besides Charles XII were his close friend Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld, also Magnus Stenbock and Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt.

Charles Frederick, son of Frederick IV, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (a cousin of Charles XII)[nb 1] and Hedvig Sophia, daughter of Charles XI of Sweden, had been the Swedish heir since 1702. He claimed the throne upon Charles XII's death in 1718, but was supplanted by Ulrike Eleonora. Charles Frederick was married to a daughter of Peter I, Anna Petrovna.

Ivan Mazepa was a Ukrainian Cossack hetman who fought for Russia but defected to Charles XII in 1708. Mazepa died in 1709 in Ottoman exile.

Allied camp

Augustus II of Poland (left) and Frederick William I of Prussia (right)

Peter the Great became Tsar in 1682 upon the death of his elder brother Feodor but did not become the actual ruler until 1689. He commenced reforming the country, turning the Russian tsardom into a modernized empire relying on trade and on a strong, professional army and navy. He greatly expanded the size of Russia during his reign while providing access to the Baltic, Black, and Caspian seas. Beside Peter, the principal Russian commanders were Aleksandr Danilovich Menshikov and Boris Sheremetev.

Augustus II the Strong, elector of Saxony and another cousin of Charles XII,[nb 1] gained the Polish crown after the death of King John III Sobieski in 1696. His ambitions to transform the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth into an absolute monarchy were not realized due to the zealous nature of the Polish nobility and the previously initiated laws that decreased the power of the monarch. His meeting with Peter the Great in Rawa Ruska in September 1698, where the plans to attack Sweden were made, became legendary for its decadence.

Frederick IV of Denmark-Norway, another cousin of Charles XII,[nb 1] succeeded Christian V in 1699 and continued his anti-Swedish policies. After the setbacks of 1700, he focused on transforming his state, an absolute monarchy, in a manner similar to Charles XI of Sweden. He did not achieve his main goal: to regain the former eastern Danish provinces lost to Sweden in the course of the 17th century. He was not able to keep northern Swedish Pomerania, Danish from 1712 to 1715. He did put an end to the Swedish threat south of Denmark. He ended Sweden's exemption from the Sound Dues (transit taxes/tariffs on cargo moved between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea).

Frederick William I entered the war as elector of Brandenburg and king in Prussia – the royal title had been secured in 1701. He was determined to gain the Oder estuary with its access to the Baltic Sea for the Brandenburgian core areas, which had been a state goal for centuries.

George I of the House of Hanover, elector of Hanover and, since 1714, king of Great Britain and of Ireland, took the opportunity to connect his landlocked German electorate to the North Sea.

Army size

In 1700, Charles XII had a standing army of 77,000 men (based on annual training). By 1707 this number had swollen to at least 120,000 despite casualties.

Russia was able to mobilize a larger army but could not put all of it into action simultaneously. The Russian mobilization system was ineffective and the expanding nation needed to be defended in many locations. A grand mobilization covering Russia's vast territories would have been unrealistic. Peter I tried to raise his army's morale to Swedish levels. Denmark contributed 20,000 men in their invasion of Holstein-Gottorp and more on other fronts. Poland and Saxony together could mobilize at least 100,000 men.

1700: Denmark, Riga and Narva

Main articles: Siege of Tönning, Landing on Humlebæk, Peace of Travendal, and Battle of Narva (1700)

The bombardment of Copenhagen, 1700

Frederik IV of Denmark–Norway directed his first attack against Sweden's ally Holstein-Gottorp. In March 1700, a Danish army laid siege to Tönning.[19] Simultaneously, Augustus II's forces advanced through Swedish Livonia, captured Dünamünde and laid siege to Riga.[20]

Charles XII of Sweden first focused on attacking Denmark. The Swedish navy was able to outmaneuver the Danish Sound blockade and deploy an army near the Danish capital, Copenhagen. At the same time, a combined Anglo-Dutch fleet had also set course towards Denmark. Together with the Swedish fleet, they carried out a bombardment of Copenhagen from 20 to 26 July. This surprise move and pressure by the Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) forced Denmark–Norway to withdraw from the war in August 1700 according to the terms of the Peace of Travendal.[21]

Charles XII was now able to speedily deploy his army to the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea and face his remaining enemies: besides the army of Augustus II in Livonia, an army of Russian tsar Peter I was already on its way to invade Swedish Ingria,[21] where it laid siege to Narva in October. In November, the Russian and Swedish armies met at the First Battle of Narva where the Russians suffered a crushing defeat.[22]

After the dissolution of the first coalition through the peace of Travendal and with the victory at Narva; the Swedish chancellor, Benedict Oxenstjerna, attempted to use the bidding for the favour of Sweden by France and the Maritime Powers (then on the eve of the War of the Spanish Succession)[17] to end the war and make Charles an arbiter of Europe.

1701–1706: Poland-Lithuania and Saxony

Main articles: Crossing of the Düna, Battle of Kliszów, Battle of Fraustadt, Battle of Kalisz, Civil war in Poland (1704–1706), Treaty of Narva, Campaign of Grodno, Treaty of Warsaw (1705), and Treaty of Altranstädt (1706)

Battle of Riga, the first major battle of the Swedish invasion of Poland, 1701

Charles XII then turned south to meet Augustus II, Elector of Saxony, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was formally neutral at this point, as Augustus started the war as an Elector of Saxony. Disregarding Polish negotiation proposals supported by the Swedish parliament, Charles crossed into the Commonwealth and decisively defeated the Saxe-Polish forces in the Battle of Klissow in 1702 and in the Battle of Pultusk in 1703. This successful invasion enabled Charles XII to dethrone Augustus II and coerce the Polish sejm to replace him with Stanislaus Leszczyński in 1704.[23] August II resisted, still possessing control of his native Saxony, but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Fraustadt in 1706, a battle sometimes compared to the Ancient Battle of Cannae due to the Swedish forces' use of double envelopment, with a deadly result for the Saxon army. August II was forced to sign the Treaty of Altranstädt in 1706 in which he made peace with the Swedish Empire,[24] renounced his claims to the Polish crown, accepted Stanislaus Leszczyński as king, and ended his alliance with Russia. Patkul was also extradited and executed by breaking on the wheel in 1707, an incident which, given his diplomatic immunity, infuriated opinion against the Swedish king, who was then expected to win the war against the only hostile power remaining, Tsar Peter's Russia.[25]

1702–1710: Russia and the Baltic provinces

Main articles: Battle of Erastfer, Charles XII invasion of Russia, Battle of Holowczyn, Battle of Malatitze, Battle of Lesnaya, Pursuit of Krasnokutsk, Battle of Poltava, and Capitulation of Estonia and Livonia

Peter the Great assaults the island fortress of Nöteborg, which he renamed Shlisselburg, recognising it as the "key" to taking Ingria.

Decisive Russian victory at Poltava 1709

The Battle of Narva dealt a severe setback to Peter the Great, but the shift of Charles XII's army to the Polish-Saxon threat soon afterward provided him with an opportunity to regroup and regain territory in the Baltic provinces. Russian victories at Erastfer and Nöteborg (Shlisselburg) provided access to Ingria in 1703, where Peter captured the Swedish fortress of Nyen, guarding the mouth of the River Neva.[26] Thanks to General Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt, whose outnumbered forces fended the Russians off in the battles of Gemäuerthof and Jakobstadt, Sweden was able to maintain control of most of its Baltic provinces. Before going to war, Peter had made preparations for a navy and a modern-style army, based primarily on infantry drilled in the use of firearms.

The Nyen fortress was soon abandoned and demolished by Peter, who built nearby a superior fortress as a beginning to the city of Saint Petersburg. By 1704, other fortresses were situated on the island of Kotlin and the sand flats to its south. These became known as Kronstadt and Kronslot.[26] The Swedes attempted a raid on the Neva fort on 13 July 1704 with ships and landing armies, but the Russian fortifications held. In 1705, repeated Swedish attacks were made against Russian fortifications in the area, to little effect. A major attack on 15 July 1705 ended in the deaths of more than 500 Swedish men, or a third of its forces[27]

In view of continued failure to check Russian consolidation, and with declining manpower, Sweden opted to blockade Saint Petersburg in 1705. In the summer of 1706, Swedish General Georg Johan Maidel crossed the Neva with 4,000 troops and defeated an opposing Russian force, but made no move on Saint Petersburg. Later in the autumn Peter I led an army of 20,000 men in an attempt to take the Swedish town and fortress of Viborg. However, bad roads proved impassable to his heavy siege guns. The troops, who arrived on 12 October, therefore had to abandon the siege after only a few days. On 12 May 1708, a Russian galley fleet made a lightning raid on Borgå and managed to return to Kronslot just one day before the Swedish battle fleet returned to the blockade, after being delayed by unfavourable winds.

In August 1708, a Swedish army of 12,000 men under General Georg Henrik Lybecker attacked Ingria, crossing the Neva from the north. They met stubborn resistance, ran out of supplies and, after reaching the Gulf of Finland west of Kronstadt, had to be evacuated by sea between 10 and 17 October. Over 11,000 men were evacuated but more than 5000 horses were slaughtered, which crippled the mobility and offensive capability of the Swedish army in Finland for several years. Peter I took advantage of this by redeploying a large number of men from Ingria to Ukraine.[28]

Charles spent the years 1702–06 in a prolonged struggle with Augustus II the Strong; he had already inflicted defeat on him at Riga in June 1701 and took Warsaw the following year, but trying to force a decisive defeat proved elusive. Russia left Poland in the spring of 1706, abandoning artillery but escaping from the pursuing Swedes, who stopped at Pinsk.[29] Charles wanted not just to defeat the Commonwealth army but to depose Augustus, whom he regarded as especially treasonous, and have him replaced with someone who would be a Swedish ally, though this proved hard to achieve. After years of marches and fighting around Poland he finally had to invade Augustus' hereditary Saxony to take him out of the war.[24] In the treaty of Altranstädt (1706), Augustus was finally forced to step down from the Polish throne, but Charles had already lost the valuable advantage of time over his main enemy in the east, Peter I, who then had the time to recover and build up an army that was both new and better.

At this point, in 1707, Peter offered to return everything he had so far occupied (essentially Ingria) except Saint Petersburg and the line of the Neva,[17] to avoid a full-scale war, but Charles XII refused.[30] Instead he initiated a march from Saxony to invade Russia. Though his primary goal was Moscow, the strength of his forces was sapped by the cold weather (the winter of 1708/09 being one of the most severe in modern European history)[31] and Peter's use of scorched earth tactics.[32] When the main army turned south to recover in Ukraine,[33] the second army with supplies and reinforcements was intercepted and routed at Lesnaya—and so were the supplies and reinforcements of Swedish ally Ivan Mazepa in Baturyn. Charles was crushingly defeated by a larger Russian force under Peter in the Battle of Poltava and fled to the Ottoman Empire while the remains of his army surrendered at Perevolochna.[34]

This shattering defeat in 1709 did not end the war, although it decided it. Denmark and Saxony joined the war again and Augustus the Strong, through the politics of Boris Kurakin, regained the Polish throne.[35] Peter continued his campaigns in the Baltics, and eventually he built up a powerful navy. In 1710 the Russian forces captured Riga,[36] at the time the most populated city in the Swedish realm, and Tallinn, evicting the Swedes from the Baltic provinces, now integrated in the Russian Tsardom by the capitulation of Estonia and Livonia.

Поделиться25817.12.21 12:29:12

А звука нет или это у меня комп глючит?

Поделиться25917.12.21 17:34:50

А звука нет или это у меня комп глючит?

Звук ещё не создавал. Надеюсь чуть позже сделаю.

Поделиться26118.12.21 13:13:59

Отличные "мотивы" получились!!!